Most people have a mental image of the Incas based on Machu Picchu; they see temples made of granite and stories about gold gods, but they never think about how these remarkable structures and their legends came to be. It is necessary to learn about the economy of incas if one wants to know why and how the Incas created such a vast territory and controlled millions of people living in desert, jungle, and alpine conditions throughout the Andes Mountains. When we talk about the Inca economy, we are really talking about a highly organized system where politics, society, and production were deeply connected.

The Incas were able to achieve this high level of societal organization and productivity through the use of community labor, unmatched agricultural expertise, and systematic planning by the central authority of the state. Historians argue that the economic system of the Incas represents one of the most sophisticated and successful examples of state control over an economy in the ancient world, and that the economy of the Inca was uniquely stable compared to other empires of its time.

To fully comprehend the Inca civilization, one must examine the basic components of the Inca economy, the ways in which the Inca economy was organized, and the reasons for its longevity. Only then is it possible to see how the incas economic system allowed the empire to expand and how was the inca empire organized around labor and land rather than money and markets.

What Was the Inca Economy Based On

The system used by the Incas divided their land into three groups or categories:

- Land for the Sun (religious institutions)

- Land for the Inca (the state)

- Land for the ayllu (the local families and communities)

This division meant that every Inca community farmed all three categories of agricultural land and could meet their needs through the organized sharing of resources from all three types of land. In addition, as we investigate on what was the Inca economy was based on, it becomes very clear that the way that the Inca organized both their economy and the way in which they organised their daily lives were inextricably linked to one another. These three types of land show how closely the economy of the inca empire was tied to religion, state power, and community life.

Historians generally agree that the base of the Inca economy was what we call a redistributive economy today, where goods were gathered by the state and then redistributed throughout the empire. No resources were wasted, and no one relied on the luck of the draw or market demand for their livelihood. When describing the economy of incas, scholars often emphasize that this model of redistribution was more important than trade for profit.

Additionally, many textbooks remind students that agriculture was the foundation of the economy Maya Aztec Inca, yet the Inka’s take was unique. The inka were among the first to apply smart agricultural engineering, and their systems are still studied by today’s scientists. Terracing, irrigation, soil improvements, and crop rotations were key inca economic activities; they had all of that down pat. In this sense, inca agriculture was the heart of the system, and every inca crop was planned to fit a particular altitude and microclimate.

That’s why, if we go back to what was the Inca economy based on, the complete answer would be agriculture, organized labor, communal structure, and state redistribution. All of these pieces together formed the inca economy and made the incan economy one of the most effective state-run systems in the ancient world.

Labor and Reciprocity Systems

To understand the way the inca economy worked, we need to understand the labor philosophy that held their world together. Most people today seek a simple explanation like: how did the inca economy work? The truth is surprisingly elegant and is at the center of how historians describe the incas economic system.

Three major labor systems defined the empire and formed the core of the inca labor system:

Ayni: Reciprocity Between Families

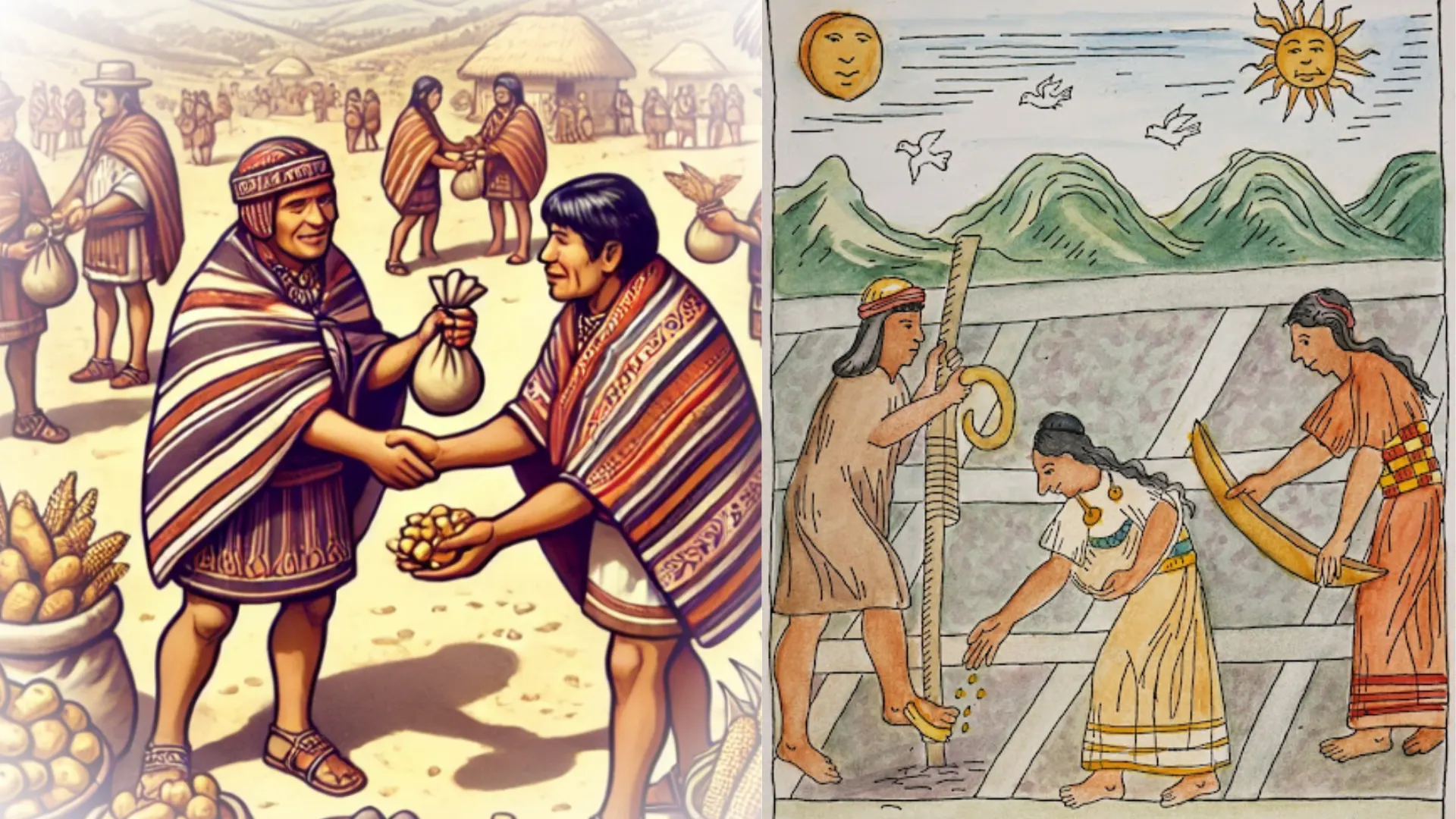

The relationship called Ayni represented the basis of the moral structure of Andean societies. Everyone depended on someone; there was no independent existence within an Andean world. By establishing Ayni, if I assisted you to plant your potatoes, you helped me later to gather them. If a person was sick or a family member had a roof issue, the whole community came together to help out, knowing they would rely on the community for the same type of assistance at some point in the future.

Long before the word safety net was ever used, this system provided a way for people to ensure safety, security, and food for their families. The principle of Ayni extended to many life events such as marriage, burial, home building, and the agricultural calendar. The principle of Ayni supported everyone in the community so that no family was without something to keep them productive. As evidenced by the continuing use of the tradition of Ayni in many Andean communities today, this tradition has continued through many generationsand remains a living example of how the economy incas depended on reciprocity, not money.

Minka : Communal Labor for the Community

Minka (or Minga), which refers to mutual cooperation among individuals and families, was a way to build community cooperatively around the purpose of completing projects of mutual benefit to all members of that community. Minka activities provided the necessary infrastructure for any given village to exist and operate. Some examples of Minka are repairing or upgrading irrigation canals after heavy rains, constructing terracing for farming inca, cleaning up roads and walkways, and restoring and refurbishing public buildings (e.g., churches, schools) and preparing fields for planting during the main agricultural growing seasons.

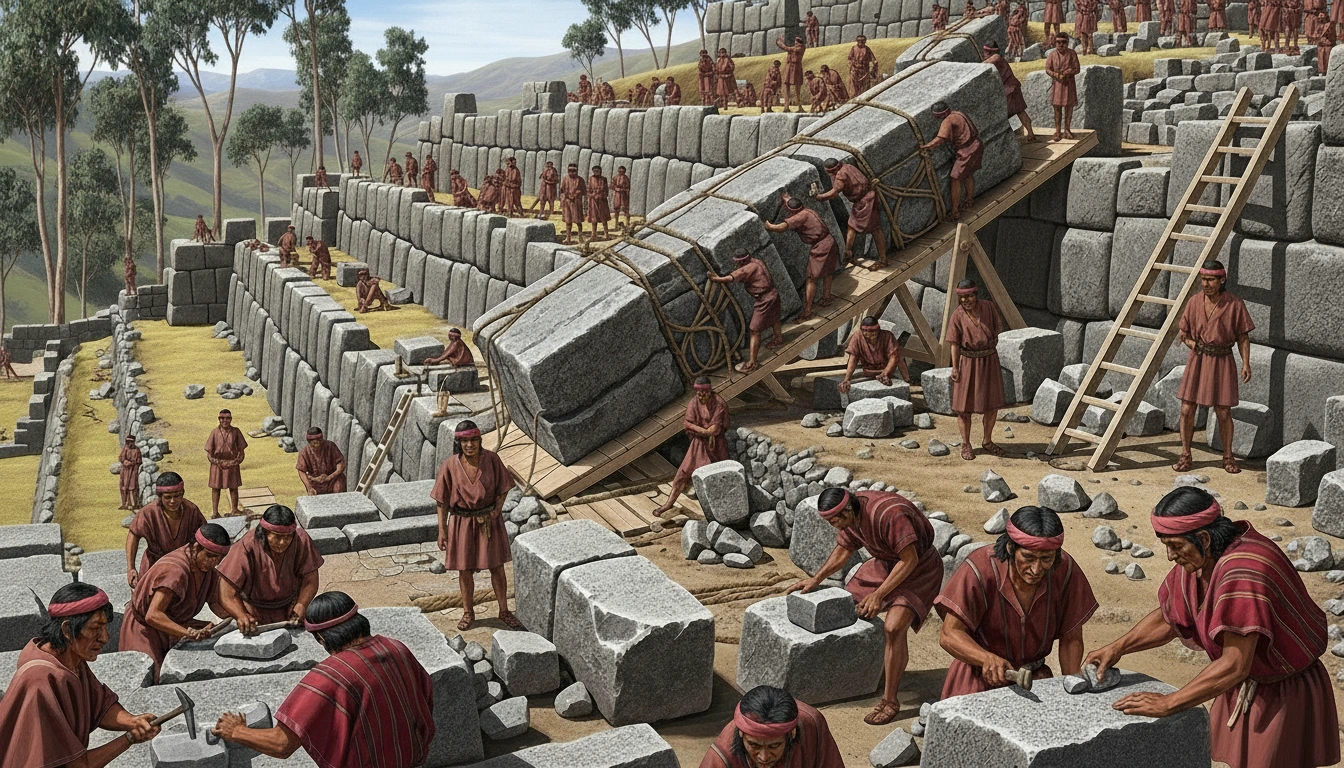

Minka served the purpose of helping to develop a community’s collective identity and to prevent critical infrastructure from falling into disrepair. Therefore, all people participated in Minka without being paid; no one expected an individual benefit, and participation in Minka was seen as a civic duty and honour. Through Minka, large infrastructure projects (agricultural terraces, stone walls, irrigation systems) were able to be built and maintained for generations. These projects are a direct example of how the incan empire economy used collective work for public benefit.

The scale of some Minka projects is astonishing. Whole mountain slopes were reshaped using terrace systems (andenes), many of which are still used today. These communal efforts allowed the Inca Empire to maximize food production even in harsh mountain environments, and they illustrate perfectly how the inca labor system supported both local needs and state priorities.

Some of the Inca Empire’s projects were remarkable for their size, and some of the Minka projects are particularly impressive. The Inca had an extensive system (andenes) of terracing systems that reshaped mountains into terraced slopes, many of which are still in use today. The community based approach of the Minka allowed the Inca Empire to maximize their food production in some of the most inhospitable areas of the world the mountains showing how inca economic activities always linked labor, land, and survival.

Mit’a : Labor Tax for the State

The Mit’a System was one of the three labor systems available to the Inca. It was by far the most structured and organized. The Mit’a System can be defined as a labor tax that every able bodied adult was required to provide to the Inca State for a specified number of days each year. Instead of money being used as payment, as there was no monetary system in place, the population of the Inca Empire paid their taxes with physical labor. This mit’a labor system is one of the most important pillars of the economy of the inca and is often cited as a defining trait of the incan economy.

Mit’a labor was used for:

- building and repairing the 40,000 km Inca Road System

- constructing temples, administrative centers, and fortresses

- producing textiles for the army and state ceremonies

- maintaining agricultural terraces and irrigation canals

- mining precious metals for religious purposes

- serving in the military

- transporting goods with llama caravans

- working in storage centers (qullqas)

While serving in their capacity as workers to the state, the workers were provided with food, clothing, and shelter by the state so that none would suffer from economic hardship while performing their duties. Furthermore, through the Mit’a system of labor, empires have experienced rapid growth; developed substantial infrastructure without having any need for slavery or a monetary system. For teachers who ask in exams which of the following accurately describes one major way the inca were able to achieve significant building projects?, the correct answer always points to the mit’a labor system and its central role in the incas trade of labor for security.

Machu Picchu, Sacsayhuamán, Ollantaytambo, Pisac, and many other roads and terraces are just a few examples of what the Mit’a enabled to come into existence. It was the engine that kept the empire unified and functioning and is at the heart of how did the inca economy work in practice.

Comparative Overview of Ayni, Minka, and Mit’a

The three labor systems served as the foundation of Inca Economic Life, impacting how people within each community interacted with one other, how responsibilities were divided and shared between individuals and the State, and ultimately how an economic system supported the State as a whole. The Ayni, Minka, and Mit’a provided a structural framework that organised Inca daily existence, ensured the development of infrastructure, and ensured the survival of the empire by illustrating the highly cooperative and well organised nature of Inca Culture. Together, they explain why the economy of the inca empire could function without money and how was the inca empire organized from the local level upward.

| System | Core Meaning | Who Participated | Main Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayni | Reciprocal help between families. | Neighbors and relatives. | Mutual support in daily life. | Planting/harvesting, house repairs, helping during illness. |

| Minka | Collective labor for the community. | Entire community (ayllu). | Build and maintain shared infrastructure. | Irrigation canals, terraces, roads, communal buildings. |

| Mit’a | Mandatory labor tax for the state. | All ablebodied adults. | Support imperial projects and administration. | Roads, temples, storage houses, mining, military service. |

Agriculture as the Foundation

Numerous historians state that Agriculture was the basis for the economy of the ancient world; the Inca Civilisation clearly illustrates this point. The Andes Region is perhaps the most brutal environment for agricultural production cold, steep, thin air, very unpredictable weather and yet the Incas were able to provide food for millions. This is why so many descriptions of the economy of incas start with inca agriculture and the genius of farming inca highlands.

Here is where the Incas showed genius:

- Terracing (andene) reduced soil erosion.

- Irrigation canals stored glacial meltwater.

- Food was stored for many years using storage systems.

- Different growing environments existed at different elevations on a single mountain.

Similarly, when scholars repeatedly refer to agriculture was the foundation of the economy, it is because without these feats of engineering, the empire could not have existed. Without inca agriculture, there would have been no surplus to support administrators, soldiers, or builders, and the entire inca trade and economy would have collapsed.

The Incas cultivated over 70 types of crops, including potatoes, maize, quinoa, chili peppers, beans, peanuts, and squash, and even medicinal herbs like coca. Each inca crop was adapted to a specific height and climate, making the most of limited soil and water. Their agriculture was so efficient that it allowed them to maintain armies, big cities, and reserves in case of emergencies. When people ask what resources did the incas have, the first answer is always land, water, and a remarkable knowledge of plants.

This agricultural innovation explains on what was the inca economy based on at its deepest level: mastery of the environment. The way the incan empire economy organized terraces, canals, and storage houses shows why inca economic activities were so successful in such a challenging landscape.

State Control and Organization

Understanding how the economy of the inca empire was organized reveals the true power of the Inca government. Almost everything passed through state planning, which is why many historians use phrases like inca trade and economy or the inca empire economy to emphasize the unity of politics and production.

People often ask: what role did the Inca government play in the economy?

The answer is simple: everything.

The state strictly controlled:

- land distribution

- labor assignments

- food storage

- textile production

- road maintenance

- llama caravans

- redistribution of goods

- census and population management

In a world without money, the government had to keep a close count of who worked, what was produced, and what was needed. This is why the Incas developed quipus, the knotted strings used for accounting. These tools helped administrators manage inca economic activities across thousands of kilometers and many ecological zones.

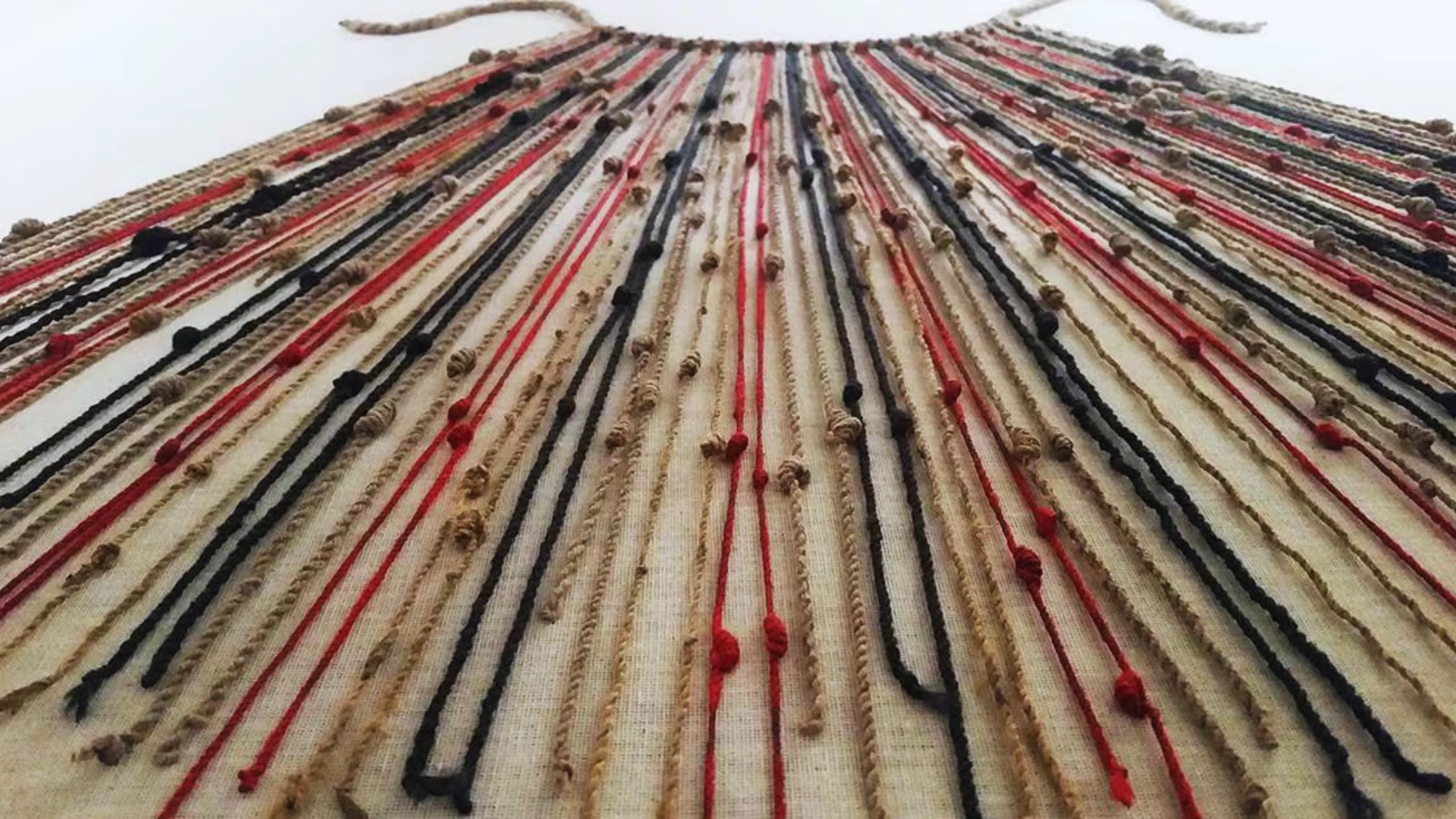

Quipus: The Inca Empire’s Record Keeping System

Inca quipus were a system of cords and knots that were the main means the Inca Empire used to store and manage their economies. Quipus enabled the Inca government to record numbers very accurately, even though there was no written language. Each knot, cord colour and location along with the measurement of each cord represented a specific piece of information.

Quipucamayocs were specialists who would read and write these records and track:

- labor contributions for the mit’a

- harvest totals and agricultural production

- storage levels in state warehouses

- population counts and census information

- distribution of goods across regions

The Inca Empire had a state accounting system that allowed the Empire to keep track of its resources, organize their labor, and operate its economy with great efficiency through the use of Quipus. Without this accounting system, it would have been impossible to maintain the overall administrative structure of the Inca Empire.

How Did the Incas Control Their Economy

People often ask how did the inca economy work. The Incas managed their economy through supervision, organization, and a vast administrative infrastructure that spanned throughout their entire empire. This structure is the primary reason the incan empire economy could function without currency or private markets.

An easy way to understand this system of managing the economy is:

The Inca administration distributed labor, organized the use of agricultural resources, produced goods, and collected all finished products at the Inca warehouses, which were referred to as qullqas.

Inspectors regularly toured around different communities to make sure they were fulfilling their obligations. The Empire was very disciplined and did not allow for any form of compliance.

The structure of the inca economy provided for both strong and weak regions and showed how was the inca empire organized around clear responsibilities and careful record keeping.

Absence of Money and Markets

Most people are shocked when they learn what type of economy did the Inca have.

The Inca’s economy was as follows:

- no currency

- no markets

- no merchants

- no buying or selling

How, then, what kind of economy did the Incas have? Or more specifically, did the incas use money?

The incan economy is based on state planned and labor distributed. All supplies and materials were provided to the common person by their government in return for labor to support the state. This makes the economy of the inca a rare example of a sophisticated system without money, where labor and redistribution replaced wages and prices.

Trade in the Inca Empire

Many researchers of ancient civilizations have studied their commercial activities, including the Incas; the question arises: what were the forms of inca civilization trade?

Trade within the Inca Empire consisted of exchanging goods, unlike trade between the Aztecs; the Incas did not have large market towns or merchant classes to facilitate trade activity. Instead, the incas economic system and trade were strictly controlled by the state. This particular form of inca trade and economy is why many historians speak of the inca trading system as administrative rather than commercial.

Trade within a specific area of the Empire was based upon local altitudinal advantages, local vegetation, and climatic conditions. The empire had over 40,000 km of roadways on which llama pack animals carried goods. These routes connected every corner of the inca empire, and inca civilization trade depended on the movement of caravans more than on merchants.

Goods Traded in the Inca Empire

Many people ask what did the inca empire trade and what did the incas trade.

Trade in the Inca Empire consisted of:

- maize and potatoes

- quinoa

- dried meat (charqui)

- salt

- coca leaves

- textiles (the most valuable Inca product)

- feathers from the Amazon

- obsidian, gold, and copper

- ceramics

- medicinal herbs

Trade was not for profit but redistribution. So, when we ask what did inca trade or what did the inca trade, the answer is that they moved essential goods for survival and ritual, not luxury items for private gain. This is why the inca trading system is always discussed together with the inca labor system and the mit’a labor system as part of one integrated structure.

How Did People Trade in the Inca Empire

Trade in the inca empire was conducted through an extensive network of barter, with government regulation and monitoring, and is one of the most unique examples of inca civilization trade in world history.

Within communities, trade typically took place through simple, face to face trueque or barter. Families exchanged the products of their labor or what they could grow based on their local ecology. For example, a farmer living at high altitude might trade his potatoes or chuño for maize grown by lowland farmers. A family who raised llamas would exchange wool or jiske (dried llama meat) for fruits, herbs, or pottery from their neighbors. Each region of the Andes contributed unique products, creating a continuing and reciprocal dependence among people living in different regions of the Andes and shaping local inca trading practices.

Although barter is often seen as an informal and chaotic method of trade, its evolution was based on social laws, the expectations of those involved and the long established ties between communities. A sense of trust between the parties involved was a key factor, as were many of the events held in local areas, such as markets and festivals, where barter exchanges were performed. These relationships worked together to build alliances and maintain community connections and help explain who did inca trade with at local and regional levels.

What Distinguished Trade in the Inca from the Aztec Empire

The difference between the two systems is significant.

Among the Aztecs, trade was commercial. They used cacao beans as currency, had big and active markets, and they relied on professional merchants called pochteca who traveled long distances and controlled much of the economic exchange.

In contrast, the Inca Empire had no currency, no private markets, and no merchant class. Instead of commercial trade, the Incas used a redistribution system whereby the state collected goods and distributed them where they were needed. Long-distance movement of goods was organized through government controlled llama caravans, not private traders. This contrast between Aztec commerce and incan trade makes clear how different these civilizations were.

The contrasting economies of the Aztec and Inca cultures serve to highlight how different the Inca way of life was to that of the Aztecs. While the Aztecs relied on a market system of trade and commerce in their economy, the Incas used a centrally planned economy based on cooperation and state managed distribution of goods rather than profit. The inca trade and economy model is therefore described as redistributive, while Aztec trade focused on profit and private merchants.

Essential Differences Between Inca and Aztec Trade

| Key Element | Inca Empire | Aztec Empire |

|---|---|---|

| Use of Money | No currency | Cacao beans used as currency |

| Markets | No private markets | Large public markets were central |

| Merchants | No merchant class | Professional merchants (pochteca) |

| Trade Model | State controlled redistribution | Commercial, profit based trade |

| Exchange Method | Barter and government distribution | Buying, selling, and bargaining |

Describing the Economic Model

Most People searching online ask: What did the Inca economy look like?

The Inca social structure allowed for an efficient way to provide for all people by working together as a society: each family knew their responsibilities as members of the community, and all societies worked collectively to provide their resources and manpower to build all the infrastructure required by the Inca; this process was very effective in preventing starvation. This cooperation is what makes the incas trade more about movement of goods than about bargaining.

When historians try to describe the economy of the Inca, Historians describe the Inca economy by focusing on five specific characteristics:

- labor based

- centrally planned

- agricultural

- communal

- redistributive

All of these components worked together to ensure a successful Inca economy. Taken together, they help us understand why the incan empire economy remained stable across such difficult geography and why inca economic structures still fascinate modern scholars.

Accurately Describes the Economy of the Incas

The phrase that best accurately describes the economy of the Incas is:

A state controlled, labor based, agricultural economy built on reciprocity, redistribution, and collective responsibility.

This definition sums up how the Inca system worked: the government organized production, communities contributed labor instead of money, and resources were shared across the empire to ensure stability. Agriculture served as the primary basis of production and the system was maintained through social obligations such as Ayni, Minka and Mit’a. It also shows clearly that the incas economic system was not built on markets, but on obligations and shared work.

Because it combined strict state planning with strong community cooperation and operated entirely without currency there is truly no modern economic model that fully resembles the Inca approach. The economy of incas stands alone as a unique experiment in organizing people, land, and resources.

What Was the Inca Economy Like

It was a very organized, stable, and community-oriented system in which every person played a role in the sustainability of the empire. Without money, the Incas were able to feed millions through planned agriculture, shared labor, and tight state planning. The economy allowed the empire to construct cities, terraces, temples, and a huge network of roads, all powered by collective work rather than profit. In this way, the inca economy was both practical and deeply social.

Food security was ensured through terracing, irrigation, and large storage centers that supplied communities during poor harvests or military campaigns. Resources were shared and redistributed, thus famine was very rare, and local communities did not become isolated or adversarial to each other. When we revisit questions like what resources did the incas have or how did the inca economy work, the same answer appears: they had land, labor, and an unmatched ability to organize both.

Frequently asked quetions about The Inca Economy: How Agriculture and Labor Powered the Empire

-

The Inca economy was based on agriculture, organized labor, and state redistribution. Farmland, terraces, irrigation canals, and communal work systems allowed the empire to feed millions across the Andes.

-

No. The Incas had no currency of any kind. Instead of buying and selling, people contributed labor and received goods through state redistribution and local barter.

-

The government collected food, textiles, tools, and raw materials, stored them in thousands of qullqas, and redistributed them where needed. Daily needs were met through cooperation and mutual support rather than commercial exchanges.

-

Labor was the core of the system. Every person contributed through Ayni (family reciprocity), Minka (communal work), and Mit’a (labor tax for the state). These systems powered construction, agriculture, and administration.

-

Ayni was a form of reciprocal help between families. If one family helped another with planting, harvesting, or building, the favor was returned later. It created social stability and guaranteed support for all.

-

Minka was community work for local infrastructure, while Mit’a was mandatory labor for the state, used to build roads, temples, and administrative centers. Minka strengthened the village; Mit’a strengthened the empire.

-

Agriculture allowed the empire to survive in harsh environments. Terraces, irrigation canals, storage centers, and crop specialization made food production reliable, supporting large populations and armies.